Where Is Amna Al-Marri? The Hidden Crisis of Kuwait’s Disappeared Women Prisoners of Conscience

The deliberate sidelining of women prisoners of conscience in Kuwait

There have been no updates or news about the detainee Amna Al-Marri, much like other women who have been forcibly detained and disappeared. In many cases, even their names and ages remain unknown, along with the most basic information about their backgrounds and identities.

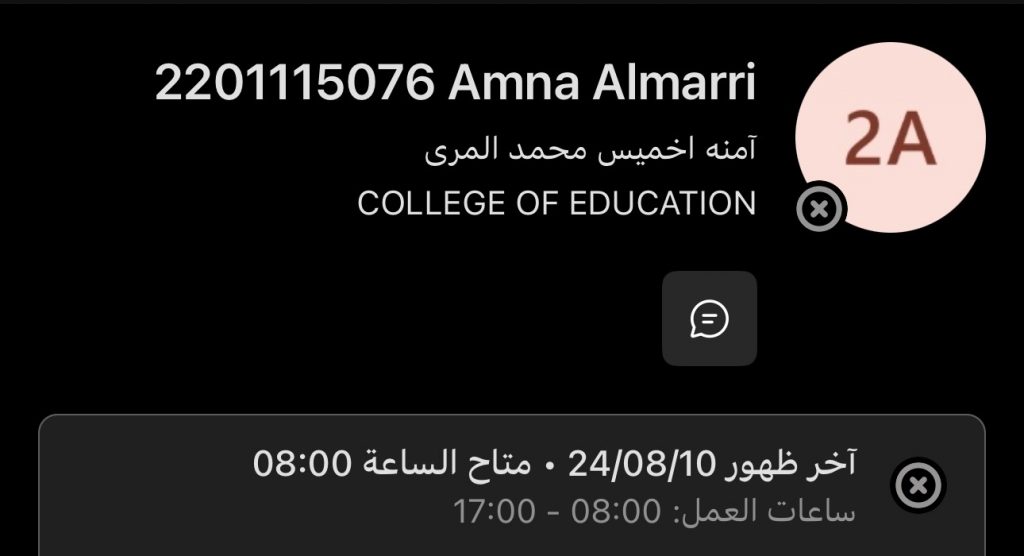

Amna Akhmees Mohammad Al-Marri is a Kuwaiti detainee whose name has circulated among activists on the platform X. According to verbal accounts, Amna lives in the Sabah Al-Ahmad area and is a university student at Kuwait University (Shadadiya campus), as suggested by the background of a widely shared image believed to show her last appearance on Microsoft Teams.

Screenshot — the last appearance of detainee Amna Al-Marri

Women in her neighborhood reportedly shared news of her arrest verbally in early 2025. Some believed it took place in February. However, her last appearance on Teams suggests she was detained as far back as August 2024.

Notably, the university did not publicly question Amna Akhmees Al-Marri’s disappearance, nor did it investigate the reasons for her absence from classes. For some observers, this silence raises troubling questions, and does not rule out institutional complicity.

How can an academic institution that teaches its students about rights, justice, and freedom of expression remain indifferent to the arrest of one of its own students? How can her peers absorb the news without concern, as if her disappearance were ordinary? And how can faculty members, professors and PhDs, stay silent in the face of such injustice, after teaching these very principles in their classrooms?

Perhaps it is unsurprising. A university that fails to uphold equal access to education for the Bidoon is unlikely to defend a prisoner of conscience. It is a stain on the reputation of any academic institution.

Friends of Amna Al-Marri describe her as ambitious and driven, an energetic, intelligent young woman whose determination extended well beyond the classroom.

“Crossing the line with His Highness”

On November 10, 2024, a Kuwaiti media platform called “Kuwait Network” published a post on X reporting that a university student had been sentenced to three years in prison. The post stated:

“The Criminal Court sentences a Kuwaiti tweeter (a university student) to three years in prison: She insulted the Amir’s authority in articles and incited the overthrow of the regime in Kuwait.”

Later, on May 19, 2025, an X account named “Al-Mudawala,” which specializes in publishing the latest legislation, rulings, and decrees, posted a similar report. It stated:

“The Court of Cassation sentences a university student to three years in prison on the charge of insulting the Amir’s authority and inciting the overthrow of the ruling system by sending posts via the Instagram application.”

Both posts describe the sentencing of a “university student” to three years on the same charges: “insulting the Amir” and “inciting the overthrow of the regime.” The first refers to her as a “tweeter,” while the second mentions “sending posts on Instagram.” While the platforms differ, the charges are identical, raising the possibility that one of these reports refers to Amna Akhmees Al-Marri. It also suggests that another student may have been detained, or that multiple cases involving university students are unfolding in parallel.

In a related case, the young woman Amna Al-Sayyid Ahmad Al-Rifa‘i was previously arrested after expressing her opinion on the issue of citizenship revocations in Kuwait. Her position reportedly subjected her to threats from a Kuwaiti citizen. Her last tweet, posted in response to those threats, was dated August 28, 2025. Since then, Amna Al-Rifa‘i has not tweeted again, and an online campaign has called for her release.

Moreover, testimonies cited in my earlier article, “Forcible arrest and the blackout imposed on Kuwaiti women,” published on the platform “Sharika Wa Laken,” pointed to patterns of blackmail and violence against women prisoners of conscience inside detention facilities. Women from the area reportedly said that Amna Akhmees Al-Marri “cries and calls out to her father for help because she is being harassed by other women prisoners inside the prison.”

Alaa Al-Saadoun… a Bidoon activist detained since 2019

In 2019, Bidoon activist Alaa Al-Saadoun was arrested for speaking publicly about the Bidoon cause and demanding her rights. At the time, the government detained her, separated her from her children, and disappeared her for an extended period inside a psychiatric hospital.

Alaa has faced a double layer of injustice and violence: first, as a Bidoon woman whose rights are systematically denied; and second, as a prisoner of conscience. To this day, her fate remains unknown, and no credible updates have been reported. She may not be the first, or the last, Bidoon woman to be detained. Many Bidoon women have been active in advocating for their rights, only to disappear from public life over time.

The Bidoon between political repression and family control

Women prisoners of conscience in Kuwait are being erased and forcibly disappeared. Their cases do not appear in public court records, and little to nothing is published about them by platforms, lawyers, or media outlets. This reflects a broader pattern of political and media repression, compounded by patriarchal pressure within society, and especially within families. In a culture where women are often stigmatized as “shame,” and where political participation itself is treated as dishonorable, the stigma attached to political detention becomes even more severe.

Kuwait is frequently described as a country that prides itself on democracy. Yet in practice, this image often appears to be little more than a carefully maintained façade, promoted by the state, echoed by the media, and reflected in institutional messaging.

For many detainees, particularly Bedouin women, release from political prison does not necessarily mean freedom. Another form of confinement may await them at home, imposed by a husband, father, brother, or even male relatives. In their view, her detention is not a violation of her rights, but a scandal that has “tainted” the family name, an accusation rarely applied to men in the same way.

In some cases, women may even face the threat of being killed “to cleanse the family’s honor,” while perpetrators benefit from reduced sentences through the falsification of psychiatric records. Patriarchy also plays a role in erasing detainees’ identities, as families fear social stigma. The state, too, reinforces this erasure by pressuring families, through coercion and intimidation, not to publish names. As a result, families often remain silent, not only out of shame, but out of fear.

Despite the publication of Amna Akhmees Mohammad Al-Marri’s name, no meaningful response has emerged from the institutions that claim to champion women’s rights and justice, not even a single statement or public post.

Kuwait’s official discourse continues to celebrate democracy, but the rhetoric rarely moves beyond surface-level messaging. While the country competes with other Gulf states in arresting prisoners of conscience, many women’s and human rights organizations remain conspicuously silent, despite being presented as advocates of justice, such as the Kuwaiti Democratic Women’s Bloc, the Progressive Movement, the Women’s Association, and others.

Once again, the fate of women prisoners of conscience in Kuwait remains absent from public discussion. Even after Amna Akhmees Mohammad Al-Marri’s name became known, these entities offered no visible engagement, no statement, no post, no acknowledgment. This silence, coupled with shallow public rhetoric, does not serve people’s struggles, advance justice, or protect rights.

Voices must be raised, and freedom must be demanded for women prisoners of conscience in Kuwait, women erased from public view and cut off from the world. Because when detainees are hidden and their stories suppressed, it is not only bodies that are imprisoned, but truth itself.

By: Dhabya Al-Yami (pseudonym)